The fifty-five years since John F. Kennedy was assassinated has seen his standing rise considerably among both historians and the general public, even putting him into the

On the face of it, Kennedy and King had virtually nothing in common. Kennedy was the Massachusetts scion of wealth and privilege, a war hero who had become President of the United States, arguably the most powerful man on the planet. King was a Baptist minister and activist from Georgia, an African American born into a permanent racial underclass—which meant a status that was harshly and often brutally defined in the American south—who assumed an increasingly central role in the leadership of the Civil Rights movement. But there were indeed commonalities. Both were handsome, charismatic figures with natural leadership qualities strengthened by conviction but tempered by a strong sense of the achievable, and validated by remarkable personal courage: King was frequently roughed up and jailed, which he bore with great equanimity; when his PT boat was lost in the Pacific in World War II, Kennedy swam three and a half miles over a four hour stretch towing a badly injured crewman to safety with a life jacket strap clenched between his teeth. Both men were highly educated, cultivated intellects with superlative written and rhetorical skills. Each were centrist figures subjected to frequent attacks from their flanks. King was pressured to go slower by more conservative blacks unnerved by the hostility and violence the Civil Rights movement provoked, while also subjected to ridicule as a celebrity with few real achievements for the wider community by African Americans becoming increasingly radicalized by that very hostility and violence unleashed by white politicians and police upon helpless protesters sworn to King’s vision of nonviolent protest. Kennedy was ever beset by attacks from his political left and right, sometimes mocked for showing “more profile than courage”—in a jab at the title of his Pulitzer Prize winning book, Profiles in Courage—as he navigated a tumultuous crisis-driven tenure dominated by pressing foreign exigencies.

Preoccupied with Soviet Premier Khrushchev’s brinksmanship and a Cold War that grew increasingly hotter by the moment, JFK dodged Civil Rights as a domestic distraction that he could not afford to dwell upon. Unlike Eisenhower, his immediate predecessor, racism was not a part of his DNA, but neither did he view Civil Rights as the great moral crusade of his time. Sensitive to demands for black equality and frustrated by southern intransigence in this regard, he nevertheless framed the struggle in legalistic rather than ethical terms.

By all rights, Jack Kennedy should have been more sympathetic to the plight of African Americans, still marginalized by endemic racial prejudice a century after emancipation, and frequently subjected to beatings and lynching in much of the South if they dared to challenge the status quo. After all, both of Kennedy’s grandfathers were Irish Catholic immigrants in Boston in the late antebellum era at a time when the Irish were the most despised demographic in America, so much so that the nativist Know-Nothing Party swept the Massachusetts state legislature and the governor’s office with overheated rhetoric aimed at the almost apocalyptic threat posed by the “dirty Irish.” But times change; one of those grandfathers went on become a two-term mayor of Boston. And Jack’s father, Joseph P. Kennedy, had his revenge on those who would shun him by becoming a millionaire. The older Kennedy boys experienced some bullying based on their ethnicity growing up, but were mostly insulated by their father’s wealth and position. Hatred of the Irish faded, but their Catholicism remained a social obstacle; JFK barely edged out lingering religious bigotry to win the presidency in 1960. Interestingly, it was Robert Kennedy—brother, Attorney General, and closest advisor to the President—who saw social acceptance of African Americans over time through this lens, even with prescience suggesting that a black man could obtain the White House in decades to come. Ironically, Martin Luther King also had a white Irish grandfather . . .

Kennedy and King first crossed paths with a tangential yet pivotal telephone call of sympathy and support that then-candidate Kennedy made to King’s pregnant wife on the eve of the presidential election, while King was jailed for his part in a protest, his fate uncertain. There was inevitably some political calculation in this—JFK was a master politician—as he lobbied for black voters in the north who tended to favor his Republican opponent, Richard Nixon. But there was more, as well: Kennedy was struck by the unfairness of King’s treatment, and there was indeed a greater risk of alienating the solidly segregationist Democratic South by reaching out to King’s family, which is why the call was opposed by nearly every member of his campaign. That phone call was to be historic, and in that narrow race black votes may have been crucial to the outcome.

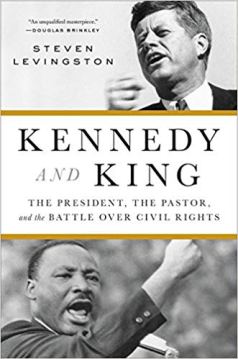

In an outstanding narrative, Levingston charts how that call, lasting less than ninety seconds, served as foundation to an uneasy relationship that often had the two men dancing around rather than with each other on the national stage, each sensitive to the other’s position but often disappointed that one would not follow where the other sought to lead. Yet, as the author deftly demonstrates, Kennedy evolved in Civil Rights as he evolved in nearly every arena. Some have suggested that JFK was dragged kicking and screaming to stand with a cause that was righteous and belated. While there may be some merit to that point of view, it lacks the appropriate nuance and complexity and context that is neatly enriched by Levingston’s analysis. Kennedy did, at root, care about black oppression, but he would have preferred to postpone the fight, at least until after his 1964 reelection, when he would no longer have to risk retaliation at the ballot box by white Southern Democrats. Of course, neither Dr. King nor rival African American leaders were willing to wait any further for long overdue justice. Moreover, as Levingston reports, there was a good deal of jockeying behind the scenes that JFK does not often receive credit for, much of it spearheaded by Robert Kennedy, who hardly could have acted without his brother’s blessing and encouragement. Also noteworthy is that perhaps more blacks were welcomed to the Kennedy White House for both business and social occasions than at any time since Lincoln was President. JFK may be accused of taking baby steps, but these were giant leaps compared to those who came before him, especially Eisenhower, who did virtually nothing to advance African American equality during his eight years in office.

In the end, as detailed in a chapter entitled with a Kennedy quote—“It Often Helps Me to be Pushed”—the President did step up to the bully pulpit and champion the cause with a televised speech to the nation, reminding the audience that America “was founded on the principle that all men are created equal, and that the rights of every man are diminished when the rights of one man are threatened.” And there was a new commitment to Civil Rights legislation. During the subsequent March on Washington in which King delivered his legendary “I Have a Dream” speech, African American White House doorman Preston Bruce, who was with the President, recalled that “an emotional John Kennedy gripped the windowsill so firmly his knuckles blanched. ‘Oh Bruce,’ he told the doorman, ‘I wish I was out there with them.’”

There is some irony that JFK walked a similar razor’s edge with his slow embrace of Civil Rights that Lincoln did with emancipation a century before, and his legacy—like Lincoln’s—has suffered for it. And, often unacknowledged, both men had their reasons. For Lincoln, it was the Civil War that posed an existential threat to the nation’s survival; he abhorred slavery, but would let it be if he could save the Union. For Kennedy, it was perhaps an even greater menace, that of nuclear annihilation, that forced JFK’s focus away from other competing issues. Like Lincoln, Kennedy was ever cognizant of principle while never losing sight of the possible. There is much to suggest that had he lived to command a second term in the White House, John F. Kennedy would have earned the praise for advancing African American equality that his untimely death denied him.

I have read numerous books about John Kennedy, an exceedingly complex character who lived his public and personal life in definitive compartments. The man and the myth are often commingled, distorting both what was and what we would like to remember. While hardly as critical or iconic to our nation’s destiny as Jefferson or Lincoln, like those two giants of American history JFK was not only brilliant but both principled and malleable. Moreover, like Jefferson he could be a mass of self-contradiction, a political acrobat poised upon opposite sides of a single issue. And like Lincoln he was forever evolving—ever “becoming,” in the parlance of Teilhard de Chardin—a new and better version of himself, until the day came, like Lincoln before him, that a bullet forever stilled that process.